OF ‘A SMALL CITY OR A LARGE VILLAGE’:

ENCOUNTERS IN ZAATARI REFUGEE CAMP, THEIR SENSE OF HOME (AND A LITTLE BIT ON COVID-19)

Post-hike essay, May 2020. Amsterdam.

The tray laden with food had been put on the tarp before I could utter or gesture, “No, thank you”. An elaborate version of that refusal, something like “No, really, thank you so much, but we are fine. You should keep your resources for you and your family” would probably have earned me a grandmotherly slap on the wrist. For 53-year-old Kulthum was a grandmother, fussing over her three grandsons in the Zaatari refugee camp.

They had fled their Syrian homelands in 2013. In Jordan her son, the grandkids’ father, had died. “He was hurt in Syria”, said Mahmoud, a gangly man of 20. He was growing into an adult, but something in his limbs seemed still a little reluctant to do so. But he wasn’t shy around us, blatant Westerners who had popped into this tiny place, our clunky hiking boots piled outside. Mahmoud poured us tea and pointed wildly with his free hand, to the wall art inside the caravan, to the bike in the back and the tiny gas-lit stove in the corner that served as a kitchen. “Stuff we made here, got here.” He spoke broken English. It didn’t deter him from saying aloud the phrases that I imagined whirled in his mind often: “If I could leave here, I would. Europe, Canada, the… US. But we don’t have money for a smuggler.” He made some income, sometimes, as a farmer’s hand. The lack of serious funds meant that the family would have to wait for an official programme.

Kulthum made it a point that her brood went to school in the camp. Her fingers traced the Anglophone letters scribbled in their brightly-coloured school notebooks. The younger ones were outside, entertaining themselves. All her grandchildren were now registered with her, she confided. “Their mother remarried. She’s somewhere here, too, but I’ve taken the kids in the last four years.” She looked pensive, then smiled, then thrust a bowl of cheese my way. “It’s for the best.” And surely, we would have breakfast - Kulthum had just finished her own meal, and not for nothing. There was more than enough to feed another two stomachs.

We went to Zaatari twice. The first visit was on a Saturday, a weekend day, and so the general staff were operating with a slimmed-down crew. Humanitarians and security officers seemed uncomfortable about letting us into the camp, even less to have us roaming around in it. "It would be best if you arrange with the managers to let you come by", the gynaecologist at the Women’s Comprehensive Health Centre said to us.

The maternity ward was no place to have unsupervised interlopers, even if she did take kindly to us and our questions. "It's as busy as you'd expect in any women's clinic anywhere. The usual case load", she said nonchalantly. "You know, the mothers need help with their children, or care after deliveries. There is nothing we don't do for them."

We were told later that up to sixty babies were born in Zaatari every week - a cultural remnant, it would seem, of the ways of rural communities where large families imply prosperity and helping hands.

"The first baby that was born, a boy, is now in second grade in school. Think of what that means!", Muhammad Taher, the chief of communications for the UN Refugee Council (UNHRC), told us. He welcomed Daniël and me on the second visit, which we had arranged officially. Our coming had been announced. Taher received us in a container subset of the camp: the sector dedicated to the administration and agencies that dictate refugees' lives.

Here, caravan-type offices are filled with the same plywood and formica-topped furniture that comes with humanitarians all over the world. It and the same old-fashioned equipment, water coolers and fans are then used to facilitate improvised managers' head offices, camp officials and operations supervisor meeting points.

In the years between this child’s birth and his going to school, Zaatari has sprawled further and further: it now houses more than 77.000 people, all from Syria. They started coming in, small groups of them, in 2012 and shortly after in vast numbers. Most of the people who have come, have stayed. The first boy is not the only pupil by a long shot: there are 22.000 students aged between 6 and 18. Within the twelve districts that make up Zaatari nowadays, there are 32 schools.

And in the meantime, the refugees’ lives have continued. It was a peculiar kind of continuation, in which everyday activities - going to school, to football games, to work, to family meals in the evening, to weddings - happened and yet, they didn’t seem to completely stick.

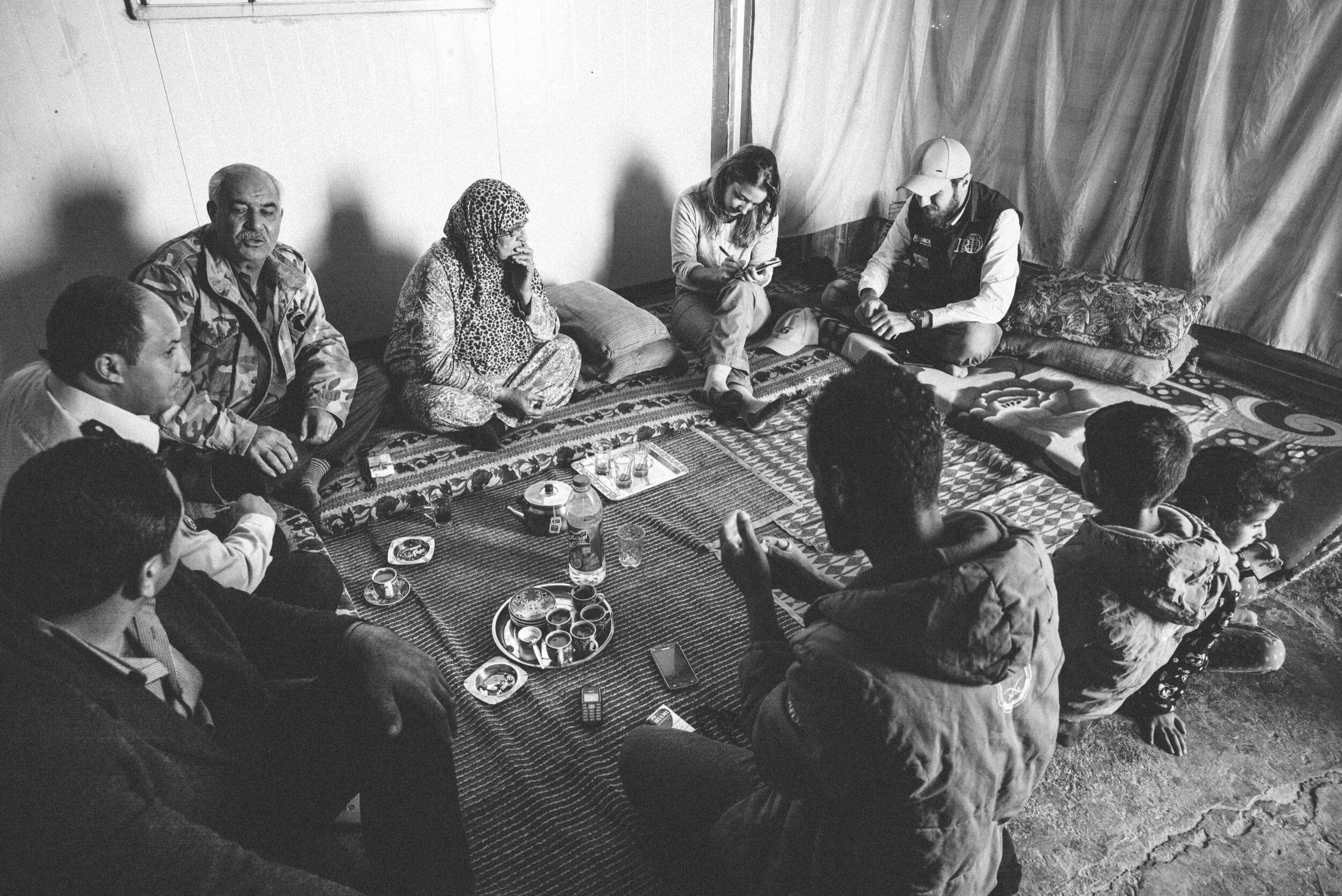

Farouk, a man in his sixties, sighed as he tried to explain that strange phenomenon. “We could complain about some things not being run perfectly. I think the education is below par, but my wife is happy our grandchildren get to go to school at all.” But hunger or services really weren’t the issue, he thought. “You want your soul to be comfortable.” Farouk’s words brought a lull to the conversation in the family home.

It was crowded in the shack that they shared. The generations were stuck together in here - a blessing as well as a nuisance. It was Daniël who saw Ahmed first: the son who had brought the the elderly couple with him to Zaatari, on the front steps of the structure. Ahmed had been on the look-out for his kids to come back from class, and his curiosity was stirred when he saw us us wandering through the camp. As the photographer and the refugee shook hands, the men communicated their names and ages - they were only one year apart. It seemed enough for Ahmed (in his forties) to invite us inside. Surely we would stay for tea and a cigarette.

We sat down on rugs and cushions, thrown on the concrete slab that served as the living room floor. This family’s village had been destroyed after they fled, their own property with it. “That is an important reason we don’t want to go back”, said Ahmed as he threw the kids’ school bags into an adjacent room. His mother, Nijma, shuddered at the thought. She didn’t have all her family here with her. All her sons fled, one of them having to bring nine children and a wife to safety. Nijma was wearing multiple layers on her body, shawls around her face. She nodded and looked up. Initially, Zaatari was a place where the family felt safe, they agreed. But now, Farouk mused on, “It feels like there is still nothing. And there will be nothing like home anymore, like my son explained. And you know, the morals affect the body.” It’s not that he was sick, the squat man in his fatigues with a sandy motif assured us. He fiddled with his mustache. It’s just that he was old, and adjusting is a hard thing to do.

This is the difficult thing to communicate to the outside world, Mr Taher knows from his experience talking to journalists and policy-makers who show up at Zaatari. It goes like this: “In the beginning of any crisis, refugees are looking only for protection. They will say, ‘I came here with my family, I don’t care about health, I don’t care about services. What I need is to just be safe with my family.’”

But it is now eight, almost nine years later. The communications chief counted the years on his fingers. There was a stern look on his face when he let his hands drop to the table between us in his prefab office. “We are talking about tertiary education, about single people who want to get married - which is their right. About people who want to get a better life.”

And right when you want to start your life again, the emergency that the larger community jumped to react to, has disappeared. New crises spring up and attention starts either to wane, or maybe some resentment arises. The outside world starts to develop donor fatigue -- I nodded, a term I know from political analyses. Donors get tired of a situation. Advocates get tired, viewers too.

Humanitarian-savant Muhammad Taher shrugged. “We try our best to keep everything going, but it is true that by now we are facing some challenges for funds.”

Now this hard place has seen a new complication hurtling its way: a global pandemic. As I sat down to write this essay, several months after our visit, I got back in touch with Mr Taher. He is still working in Zaatari, he confirmed. I texted him a request to update me on the situation in the camp: has the novel corona virus reached it yet? “Everything is good”, his answer read. “We don’t have any Covid-19 positive cases”. Schools have been closed, and people are urged to stay home, especially after six o’clock in the evenings. The agencies are working on “awareness raising”. According to the spokesman, many measures had been taken, including “disinfection at the main gate” and “random checks”. It is difficult for me to think about Zaatari as a place where life is locked down and people stay indoors.

We were driven around Zaatari refugee camp in a two-car envoy, a security officer and a non-aligned translator sent with us. The translator was Abed Keisa, an American twenty-something who had been looking for some adventure, some purpose, a way to practice his Arabic… and found himself working for the International Relief and Development programme. We shared the ring road that runs along the outskirts of the camp (and the many speed bumps) with hauling donkeys and people on bikes. The refugees were not allowed to have their own cars in the camp: the streets within were too narrow, the place would be jammed.

We passed pastel-coloured shacks decorated with the abundant symbols of international aid: bright blue hands folded in prayer, flowers and peace signs, shining stars and cool cartoon figures.

Our two minders reproached us quietly, for getting out of their decked-out cars and by turn making them trot through the muck that had formed after a recent rain shower. Our hopscotch way over the puddles brought us to Asma, a 22-year old woman with light eyes peeking out of the door of her shack, which she remained unwilling to open to us completely. We had been drawn to the house by her two young sons. The toddlers stood on the front veranda, taunting the camera, doing small-kids’ stuff.

As Asma beckoned them inside - “They have chores”, she said - her body contorted in the doorframe. Through the crack of it I could see a young baby was cradled to her chest. Her first girl, she said. “Not even a half year. My sons have to help me with her.” The third child was doing well, she nodded, the care in the center was adequate to keep her warm and fed. The baby was sleeping now, a welcome reprieve. Asma had been in Zaatari eight years, which she called “not ideal”. “It is difficult to raise kids here”, she mumbled.

A new frown formed on her forehead. The boys were being stubborn today, they had trouble listening to their parents. I made to ask about a father, but something in Asma’s face (annoyance) and the translator’s unwillingness to go there, held that question back. I struggled to jot down my notes and make out Asma’s voice over her toddlers’ drawls. The young woman had already moved on from my attempt at a conversation. Did she know about the future? Think about it? No, not really. “I need to find a place that’s good for three kids, not very easily done, don’t you think?” The door closed.

It is a human right, because it is a natural inclination that really cannot be stopped, for people to grow, to want to become different things in their lives. For some people in Zaatari, this ‘new thing’ is not so much a yearning as a prerequisite for their continued safety. In fact, there is safety in numbers in this refugee camp: in a mass of thousands, anonymity is not hard to come by. As we set out on our search for Ibrahim in Zaatari however, we were warned: to get people’s permission to take their photo; to not take down names.

These things are known, to some. In fact the Jordanian government agency that handles the refugee administration takes all of the refugees’ details, in some cases even saving biometric information. But that is information to run food deliveries, information that is the key to being granted a place to stay. It can be useful to get things organized - but in a story, and out to the world, with its potential risks? “Try not to ask too emphatically for people’s names”, Mr Taher said as he wrapped up his briefing.

It took almost two hours for our minders to give up on their planned, chauffeured tour of the camp. We convinced them to escort us to Sham Elysée; Zaatari’s elongated shopping district. Dozens of shacks and stalls line a dirt-packed street. The businesses were set up by the refugees, who accordingly were allowed to trade whatever they felt like, “as long as it’s nothing illegal”. Their wares were displayed on wooden planks or hung from the ceiling. Bicycles, food, sneakers and brightly coloured kids’ boots… This was where we found ‘our’ two Ibrahims.

The first, Ibrahim el-Hariri, had spent six years in the camp. He was 25 now, the proud owner of a barber shop. He had been studying for his bacceloreat in Syria, but this job was just, “What I do”. The shop was tiny: another shack with an open counter out front, to let the light in. His clients laughed and teased as Daniël took his picture; Ibrahim adjusted the hood of his zip-up to make good light.

The second Ibrahim asked for his name to be left out. We found him on the shopping boulevard, hauling fruits and vegetables for the grocery shop that had employed him upon his arrival seven years ago. The 27-year-old looked at his boss when I started my interview, he was distracted by the clicking of Daniël’s camera. What to do with the giant melon he had been lugging around, could someone take over? His arms fell to his sides.

When I asked who he spent his days with, a slight smile broke through: “My wife, our two children. We married two years ago. Well, two years and eight months.” He looked at me to take down the decimal. He’d worked hard at the vegetable stall to be able to afford the wedding, held in the camp. The couple had met in Zaatari.

It was all he would tell me. “I was in the army in Syria. I left, I had to leave, and now I am searched for.” I checked with Abed, who nodded curtly. “If this Ibrahim of yours returns back to where he was in Syria, he will be arrested.”

Most of those we spoke to at Shams Elysée and indeed Zaatari, had fled from Daraa, a governorate in the south-west of Syria. Many of its villages are close to Jordan.The highway that took us out of Amman towards the refugee camp leads further north to the border between the two countries. “You can almost see them from here, it feels like I could wave”, a security guard said when I asked of it. The battling was certainly noticeable when the war first spread throughout Syria, all those years ago.

For a short time after that start, these neighbouring peoples thought they could manage the conflict through acts of kindness. With trade and business relations, and in some cases even familial ties, stretching across the borders, the first Syrians to cross into Jordan in 2011 and early 2012 would rent rooms in the Jordanian Mafraq governorate or were accommodated by acquaintances. But as the violence showed no sign of subsiding, many more people continued to pour in. According to Mr Taher, the UNHCR representative: “It was really when it became 5.000 people a night, that number would never work and the camp became necessary.”

As is typical for the way in which the UNHCR operates, the Zaatari (which is only one of three camps dedicated to Syrian refugees, alone) is run jointly with the Jordanian government. It’s a combined effort that made of this massive camp a highly administrative one, which can even boast of the largest solar power plant known to the humanitarian world. While the agencies run their own power generators and pay for electricity bills, the solar park provides the energy for close to eighty thousand households - who, we were reminded by Mr Taher, fled from violence, not modern life.

“We don’t feel alone”, the elderly Farouk told us. “We cannot feel alone”, his son Ahmed mumbled as his father threw him a stern look. As he had in most of the conversation, the pater familias did the talking, stating: “Knowing that the King of Jordan cares about the refugee issue and tries to organize our stay, has a big impact on us. We feel support.” Said Ahmed: “But throw jobs into our laps, it does not. Opportunities seem to cost the most.”

The UNHRC has made it is policy not only to care for refugees, but equally to look out for the local communities that bear the brunt of the influx of newcomers, Mr Taher explained to us. Managing a refugee crisis does not come without economic challenges - even beyond securing the funds for charities to provide their ample services. Not seldom, local communities are already in demographic or economic distress. The NGO resources are not only offered to the refugees themselves, but also made available to the locals.

The government’s directions also guide the corona measures within Zaatari camp, Mr Taher explained to me over text. The evening curfew is similar to that imposed in the rest of Jordan. It means that no inhabitants are allowed to leave at all, including those who have found employment outside of the camp’s confinements. In November, Mr Taher explained that some sectors of the Jordanian labour market are opened up to refugees. Some 13,500 Zaatari residents have so far been issued a permit that allows for them to leave the camp to work. Some go back and forth every day, others might stay away for several weeks on end for manual or seasonal labour.Now, that option is off the table, he confirmed in a text, also writing: “It is temporary.”

As I type this, I look at the brightly coloured bracelet I bought at a women’s workshop in the camp. In this centre, some dozen women work to learn a trade: to make soaps and jewelry. There is a beauty salon. As I stepped into one of the trailers, a cursory glance was thrown in Daniël’s direction. A veil was quickly thrown on. “You should see it in summer, my dear”, one of the women confided in me. “All these ladies come to have their hair done.”

Since visiting the camp I have only taken that bracelet off for a two-day stretch, when the string broke on our last day in the hotel in Amman. I fixed it once I got home. It took me maybe an hour, fiddling to pull a few extra lengths of sewing thread through the beads, feeling inventive.

Such willingness to improvise is useful anywhere. But home is the place where you are guaranteed to find the stuff that will facilitate your experimentations. And if your ingenuity is called to the task of fixing a fashion accessory... that is just luxury, on top of it all.

“You know, camps are our last option”, the communications officer sighed at the top of his briefing, on that Sunday in November. These places are the last option for people - the only option for those who wait for safety to go back home and settle once again, who choose not to apply for citizenship or who cannot take the risk or spend the money to get temporarily set up in a foreign city.

Camps are the last option for the national governments that accept them on their territory, a last resort even for the UNCHR. The refugees don’t prefer to be in a camp. Living in a camp is not normal life. Even if everything they could need is provided here, all the services, it is not like having your own house, your home. It is difficult.”

Even though it was Mr Taher who compared Zaatari to a “small city, or a large village”, the camp is to remain that: a camp. At least on paper, the refugee holding pen is never to become a real thing. Covid-19 is another confusing twist in the lives of people who are in a place that is supposed to stay firmly “impermanent”, anyway.

When we were once again ushered into the car, our security minder turned to us. Surely, we could do with a quick bite before we would really leave. He knew a great falafel place on the Shams Elysée.

* Daniël and Lisa visited Zaatari refugee camp on November 16 and 17, 2019. They were received by UNHRC on November 17, and had arranged their visit with the government office for refugee administration. They were generously referred to the agency by PAX, an NGO based in the Netherlands.