The city of Urfa, on the Sanliurfa plain of the Euphrates River, has a surprise in store for us as soon as we’ve reached the town from the airport: the name of Ibrahim is scrawled in graffiti on a cobblestone wall across from our hotel. We are undeniably in the right place for our second walking stage to commence.

We take a tour through the close region of Urfa and through the history of the fourth century BC, the time period to which these early beginnings has been recorded: We visit the hive houses at Harran. The archeological site of Göbekli Tepe - presumably the remnants of an age-old temple. Its tall, upstanding stones are carved with elaborate figures, mostly of wildlife.

Urfa is known, and has been proudly referred to in our conversations, as the ‘City of Prophets’, by virtue of its ancient history as an early settlement and the early entanglement of Jewish, Islamic and Christian histories. Ideas of what is virtuous in the first place, ideas of what is sacred, have first passed through this region, brought around by these budding agricultural communities. And nowadays these are the people here: Urfa has a population of over two million, and a constant waxing and waning of pilgrims and callers. They congregate at what is rumored or believed to be the hometown of Abraham, the very place of his birth.

Abraham was born just outside of the city, in the fields, and brought up in a cave - the story goes, to shield him from the vengeance of the god-king Nimrod who has been told an impending Abraham will put an end to his idolatry. It comes to a confrontation between the two figures: Nimrod, which can be seen as misguided and misdirected polytheism (or, just pure evil), and God-acknowledging Abraham. Nimrod orders the latter to be burnt at the stake - but Abraham is saved by his belief, the fires turned to water and the logs, collected by the rulers’ subjects, becoming fish.

There is still a pond close by the Birth Cave and the adjacent mosque. Huge fish swim in the tiled basin. Day-visitors can feed them - or rather, have their children feed them, if they purchase a plastic baggie with food first.

1 October 2020: visit to Mevlid-i Halil

A special spot on our second day, with for me, a view of the women’s access to this holy site.

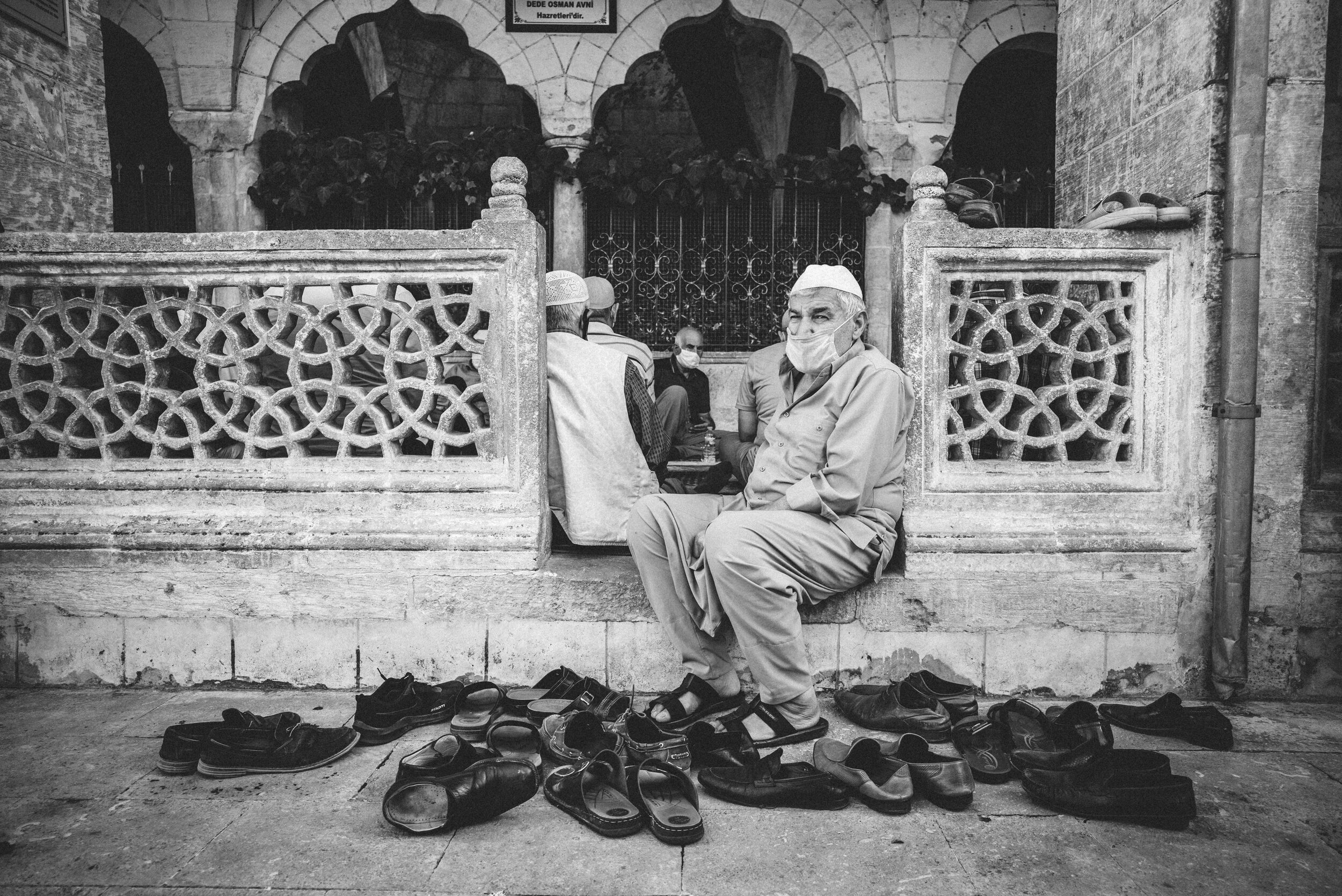

Outside: the two of us, the people, the courtyard in the park. It all seemed to be rising with the voices of a dozen men who, for minutes, persistently sing with voices that surely must be brought upward all the way to heaven. Their tribute - I’m sure it continued for long after I had visited - reverberated with every other person’s step into this domain. Children were feeding the flock of pigeons that had settled around a fountain. Their parents had bought the seeds from some vendor outside - outside of this strangely impressing place. One father lacked the patience upon seeing his daughter’s gentle, tiny hand lowering the feed to the ground. He up-ended the contained in one motion instead, showering the birds in grains to peck at.

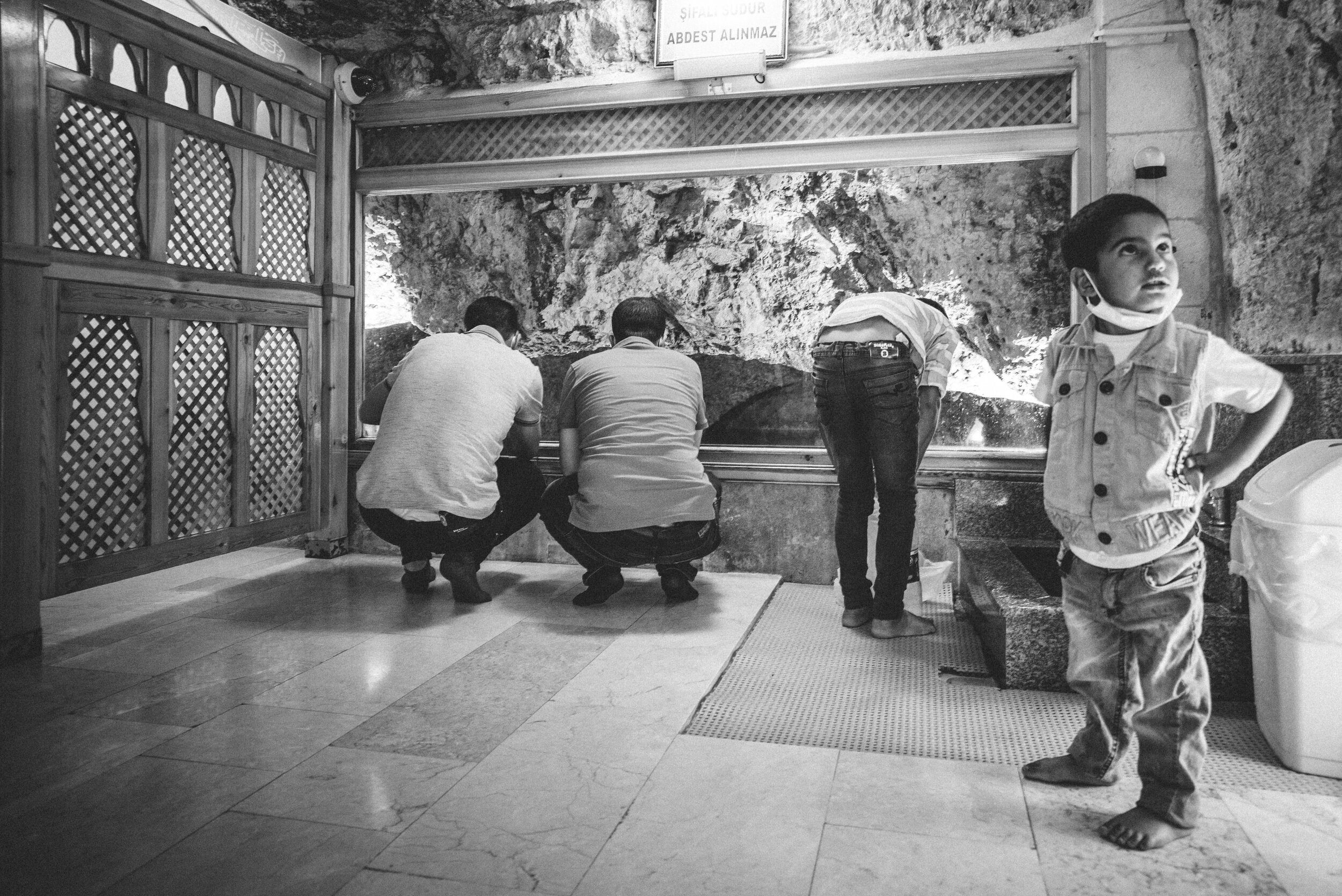

The mass of singing men, the brood of pigeons, the small sea of abandoned footwear at the cave’s entrance.

Inside: a mother gently beckoned her daughter closer to the glass window that offers a look into the cave. Once we had passed the hallway with its wooden space divider and entered through the back wall, a greenish shimmering light washed over all our faces. I had made my way following a group of five women. Several others were still inside when we joined them.

A glass wall at the back offers a view of the entrance to the cave. There is an air circulation system in the rock cavity (it must have been installed during a time before corona, I guessed). We are given this look upon a mysterious place, where Abraham saw the light of day in exile and in hiding chosen by his mother. It’s something powerful to experience this place - a mother’s chosen refuge - with only other women around.

There are hand smudges on the glass (also pre-pandemic).

The women’s headscarves bobbed before me in the passage, the cloths’ jewel greens and deep purples, swayed in my field of vision. They wore richly decorated robes. Behind us we could still make out the singing men.

The mother had taken hold of her daughter to single her out from the group, putting an arm around her shoulder. She commanded her child to rest her forehead against the wooden plinth of the window. Together they prayed, under their breaths. The older woman stroked the younger one's head, her hands on the glass, on the rock wall. She repeated the affectionate movement over and over, as if in this way she wanted to bring her daughter even closer to this special source, literally to imprint this experience of proximity to the holy source into her beloved’s body and spirit.

Meeting Ömer, imam at Mevlid-I Halil Magarasi

Within the thick walls of the imam’s office, the worshippers' reverently sung praise can still be heard as a consistent, low murmur. It is muffled through the tightly woven carpet that covers the floor and the deep sofa lined up along almost three quarters of the room, which has rounded corners. We're on the couch, sitting opposite mr Ömer, the imam at Mevlid-I Halil Magarasi. I couldn't witness his reaction when we asked for the audience spontaneously, but when the door to his office was opened a curious and intelligent - if maybe a little apprehensive - face looked out at us.

Ömer has been one of the predecessors of the mosque that next to Ibrahims Cave for the last three or four years. At 34 years old, he's remarkably young for the job. It's immediately evident that this task rests on his shoulders quite warmly, and Ömer is keen to explain the honour: “When people come to visit this site, they get to live the atmosphere of spirituality. I think the knowledge they have of coming to a place like this, it must bring them some peace. For me when I am here and when I see all the visitors, I get to witness their experience here. That is a blessing to me.” As a father with two girls, he even finds a practical version of peace in the mosque and his office.

To that end, Ömer was happy that visitors from over the world travelled to Sanliurfa to attend at the shrine. Our non-religiosity, however, does puzzle him slightly. Yet, there seems to be little effort for us in finding a topic to discuss that touches on our world and his. “You know, Islam means ‘peace’. Of course, I am well aware that there is a lot of war in this region. That would give people the wrong idea maybe, and I have thought about this. In the end, I think, it must be the intervention in the religion that makes it bad. It even says so in the Quran: ‘if you kill one person, you kill a people’. If you respect others as a human being you can put religion aside and begin to make peace. Humans must be God’s representatives, of his peace.”