8 October 2020: Leave Nizip to the young

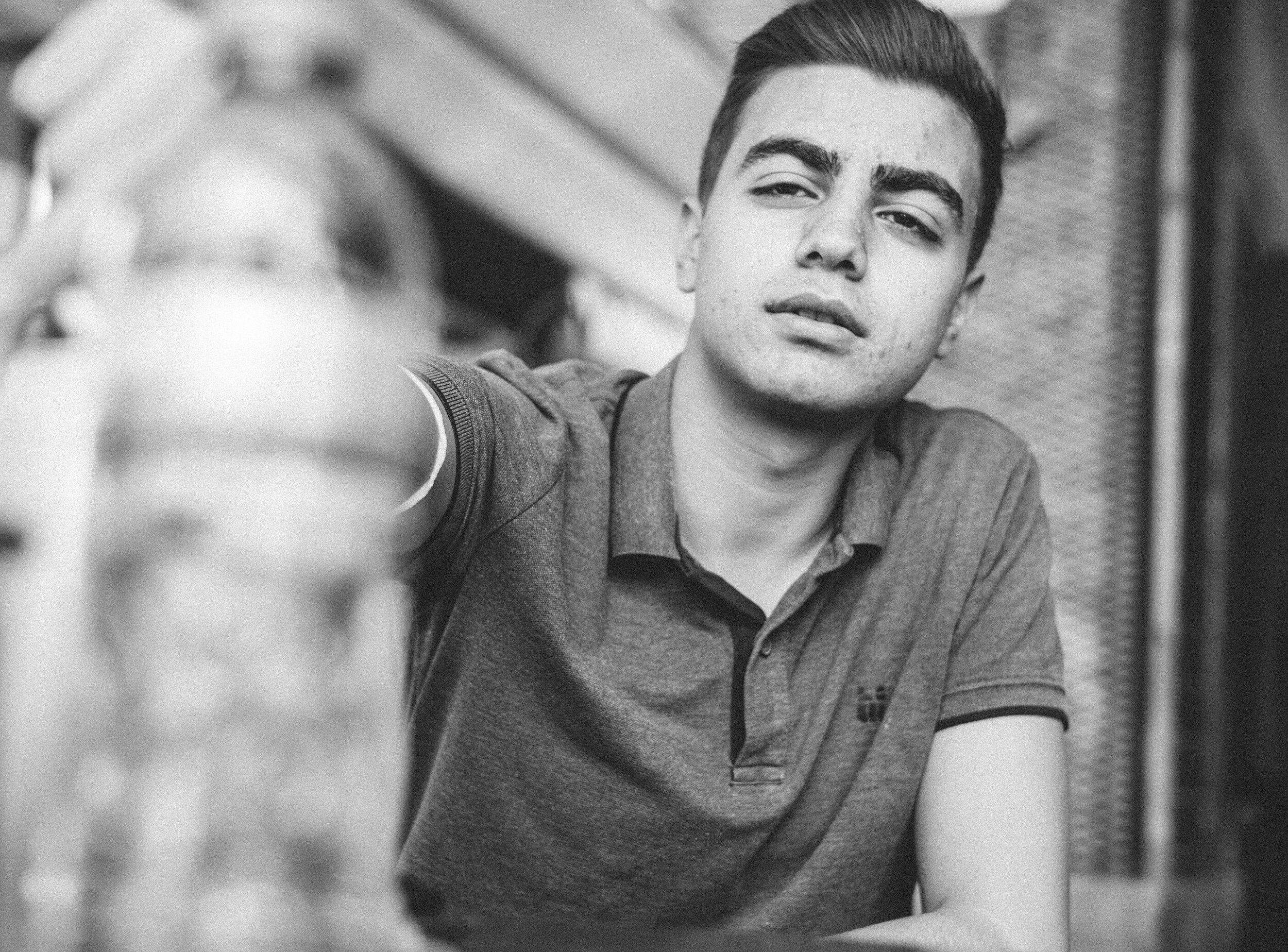

Everything that Talas (19) likes represents his longing for an ‘out’. T-shirts and music to finally let out pent-up feelings, tattoos to express your worldview constantly and proudly and a motorbike to get away from it all should those positions and your hard-fought adulthood still be met with wariness or dismissal. On that last point, the young man almost bursts with excitement when he hears that Daniel and himself prefer the same type of bike - with the considerable difference of their respective incomes and their country’s diverging general wealth, which in turn give rise to a discussion on economy. And of course economics lead to politics. Talas is impatiently waiting his first election and opportunity to vote now that he is over 18. Our discussion drifts to some of the big topics - totalitarianism, oppression -, pushed on by the ideas that he encounters on the internet, in talks with his friends and the discussions in his family. “My father is a liberal, someone who thinks for himself”, Talas says proudly. In his own mind, he’s certain that the time for a significant shift is coming. “You know, I think the sitting politicians realize this, too. They are about to lose.” The last municipal elections offer him a sliver of hope; president Erdogan’s AK Party had a hard time of it, losing popular support, to the point that some cities appear lost to its politics on the next occasion.

Talas is gauging us as his conversation partners: what can he say? What will come across as adult and contrarian, as the kind of argumentation that has been slowly simmering in his mind? Or, he has no patience left: “It is time for the young people now”, he says - when isn’t it - “and they demand to have their place. People like me. And I think, the politics will change at some point, but that is a slow process. But what we need is a better economic situation. Right now the economy is so bad, that that is what is affecting us badly most of all.”

Politics is best considered by weary people in a café, of course. Which is exactly what we are: Daniel and I are a little tired from the road, Talas is impatient with the stagnant situation he finds himself in so early in his life. Our intellectual meet-up takes place in a hip bistro on one of Nizip’s large commercial streets, where Daniel and I have wolfed down a burger and fries each. Talas’s English is really good, for which he was directed to our table by the young waiter. I suspect he had tried to eavesdrop on us before, from a gaggle of friends sat around a single board game, smoking.

At the end of the evening (me still with a body that’s shook up with PMS, so this ‘end’ comes way too early for our new friend), it’s the most natural thing to give him our phone numbers: “Take us on a tour tomorrow, show us where you go with these ideas, here in Nizip.”

When we next meet up, Talas brings his friend Khadir (18) to this mental escape. It’s a time for revisions and exam prep: their group of friends are preparing for the state’s testing program, so that they can get their spots in universities. They seem keen to leave Nizip, where they are now stuck with at their parents’ due to the epidemic, and maybe even Turkey, at least for a while. On our stroll through the city, Khadir is trying hard to see new things, the type of stuff they can show us. “I don’t know what to tell you about this place - we go to school, we go home, we can hang out to play games. There is nothing really interesting here.”

What’s more, he sees forms of aggression, conservatism, an annoying social control. “You just walk around and talk to people? Whatever does that do for you?” “We learn from them - like, you learn from us, right. You ask what we know, how life is familiar to us. So, we have the same questions to ask you.”

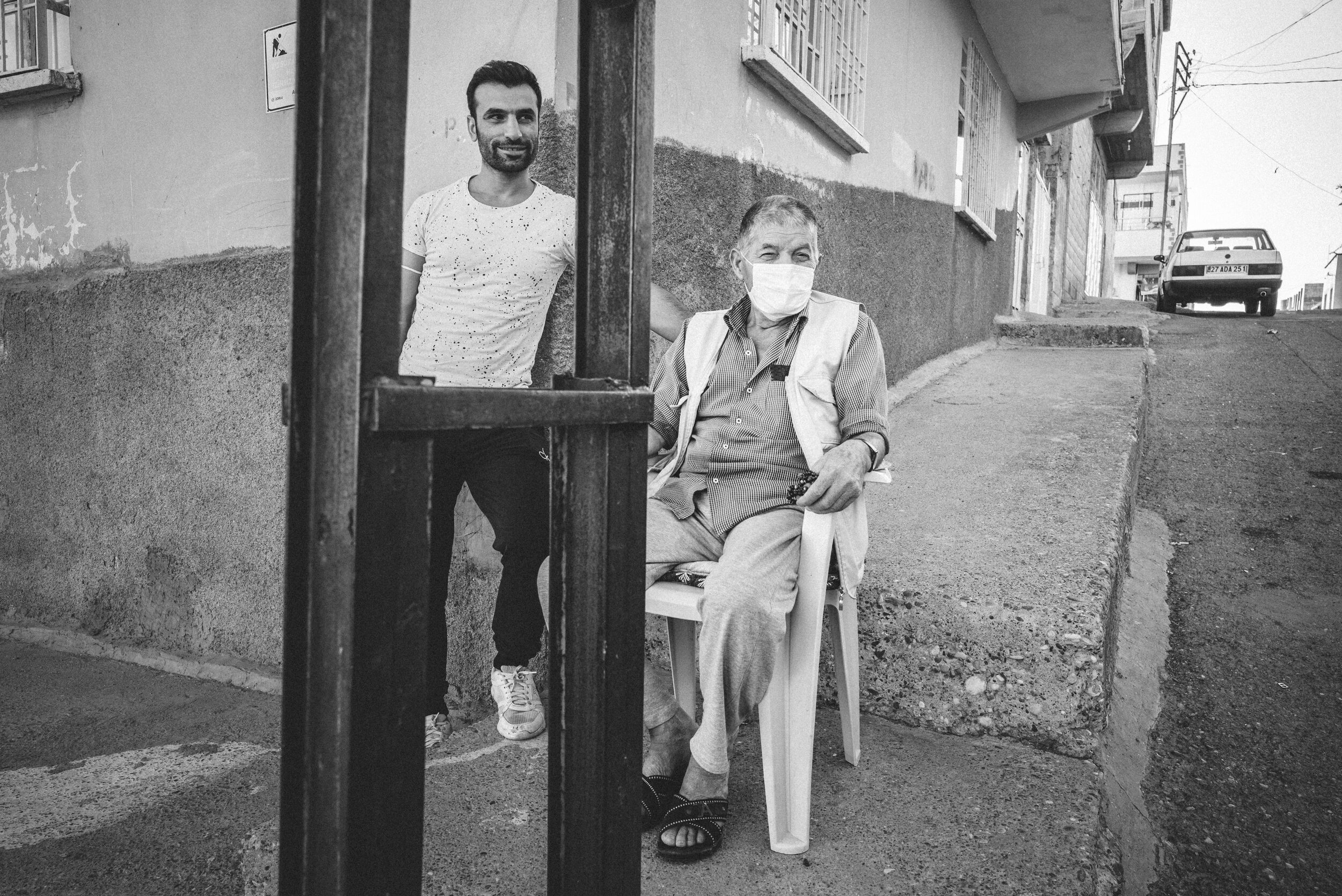

Talas and Khadir also bring us to meet two of their friends who are called Ibrahim: of similar ages and with much the same attitudes.