I feel the thud of the blue backpack strapped to my back, lunging forward as though it were making a last bid for freedom and about to leave me behind altogether. My body is feebly attempting to shift its weight, which amounts to about one-fifth of mine. This struggle is heavily impeded by the fact that one of my hiking boots is firmly wedged between a set of sandy-yellow rocks. One dried-up track of a water-current lies behind me, safely traversed.

There is another one ahead - I can see Sulaiman, our guide, and Daniël moving across it now. There will no doubt be more wadis to come today. Since I appear to be stuck here for a while longer, frustration simmering, I find myself overthinking this endeavor once more: a hike across Jordan in pursuit of something to write. The walking was supposed to bring pace to my words — the way great authors have done it, walking through landscapes to explore their minds’ expansions. So far, four days and several dozens of kilometers in, all that occupies my mind are stones, and pebbles, and rocks, the kind I was just stumbling over to follow after a donkey’s ass. It has become my strategy to stay as close as to it as possible, following its very tracks.

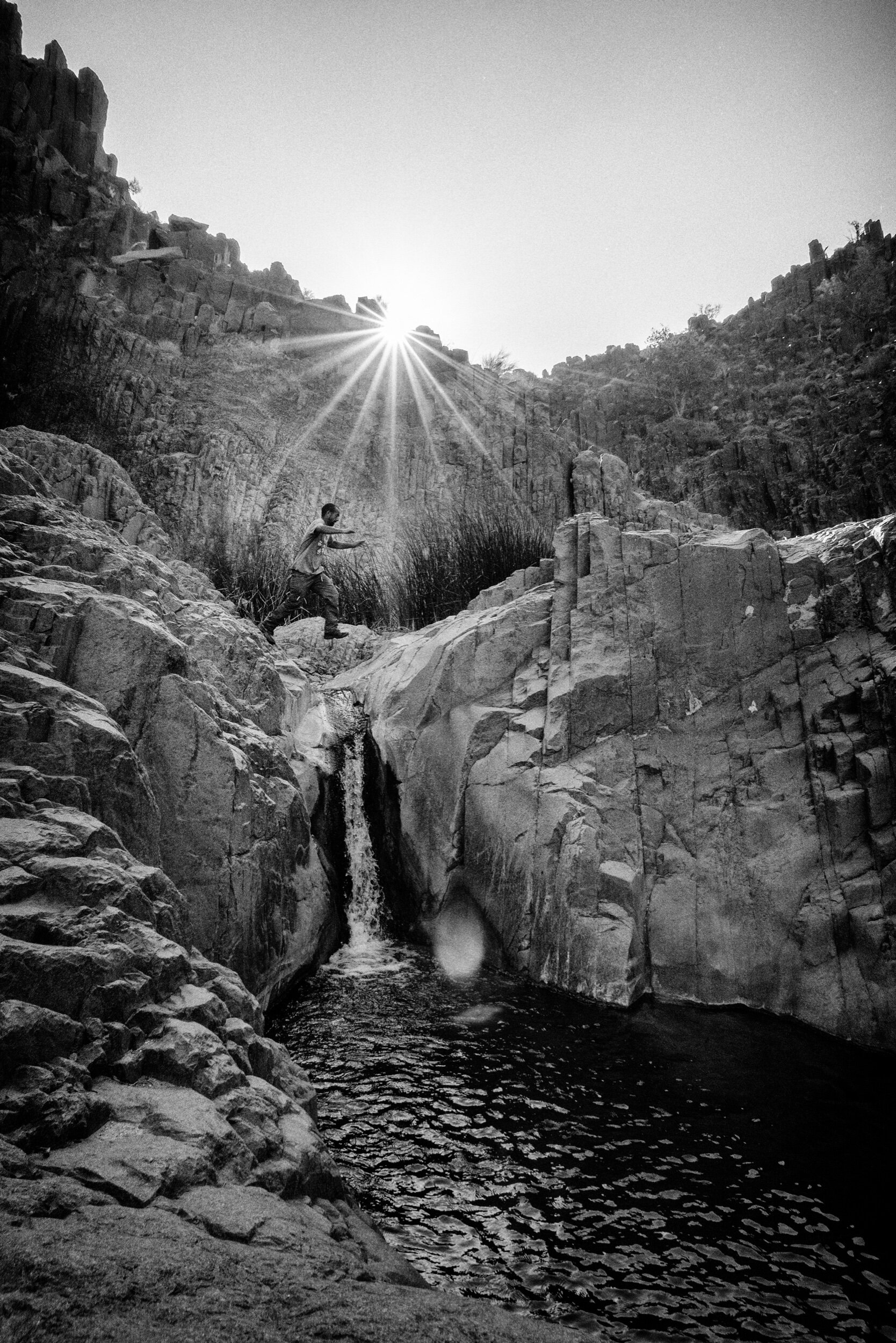

Along this trek, the country appears both wild and kind. The Dana Biosphere Reserve is Jordan’s largest nature reserve, hundreds of kilometers squared. It is composed of rocky deserts, Wadi Arabia, devoid of water over many stretches. But where it does spring up, green pops into view through the earth’s cracks. There, and on the plateaus, the country is cultivated, and herders and towns are never as far off as they seem to be. I don’t know what impresses me most: people’s ability to forge their lives in such remote areas, in the bedouin ways, or modernity’s advances to build roads and electrical plants, to place windmills and telephone poles on the steepest of mountainsides.

On the edges of Dana Reserve those two outlooks merge. The original hamlet here, now known as the Old Village, was cleared in the 1990s to make way for new, charmingly run down and boho-looking eco hotels and guest rooms. We stay in the Dana Tower Hotel after a grueling last 17-km hike uphill, the end of which we barely make without limping. A crew of men from Petra, half a day’s drive but three days walking, even bring the car down for the very last bends. They load us onto the backseat. We buy and devour a Snickers and a Coke from a tiny night shop as the price for our room is being discussed. Unfortunately we’ve just missed that evening’s dinner - a spread of rice, pasta, potatoes and fried meats and vegetables - but with the sugar already rushing through us we agree to hold out until breakfast.

We learn that a New Dana lies another kilometer or so from this travellers’ joint: it is the place to which the Dana inhabitants were asked to move when the area was labelled a cultural and environmental destination. Daniël and I are only capable of even thinking about the walk to the modern settlement one full day after our arrival to the Tower establishment. Between the two Danas lies a cemetery: the modest white tombstones have slowly accumulated on the grassy roadside.