Hot and Cold in Kilis

I was given a piece of advice, shortly before our departure to Turkey from the Netherlands. At this point there were still many days and kilometers to go before we would reach Kilis: “Kilis can be tricky, it can go from hot to cold or the other way around. The change can happen even before you get the temperature checked.”

This was not about the weather, but the political situation at this place, that is so close to the border that it can feel whatever emotions come out of the war across from it. If the conflict in Syria heats up, money and people start getting awash in Kilis. The border-post just south of the city lets through Turkish troops and equipment, in quantities as needed. The city has swelled with incoming refugees at several points in the conflict’s timeline. Foreign aid, humanitarians and non-governmental organizations or states’ development programs have added and added to it. Kilis has grown a few sizes over the years, with refugees camps close-by having been closed down in the last two or three, for Syrians with a right to settle to find or build stone houses.

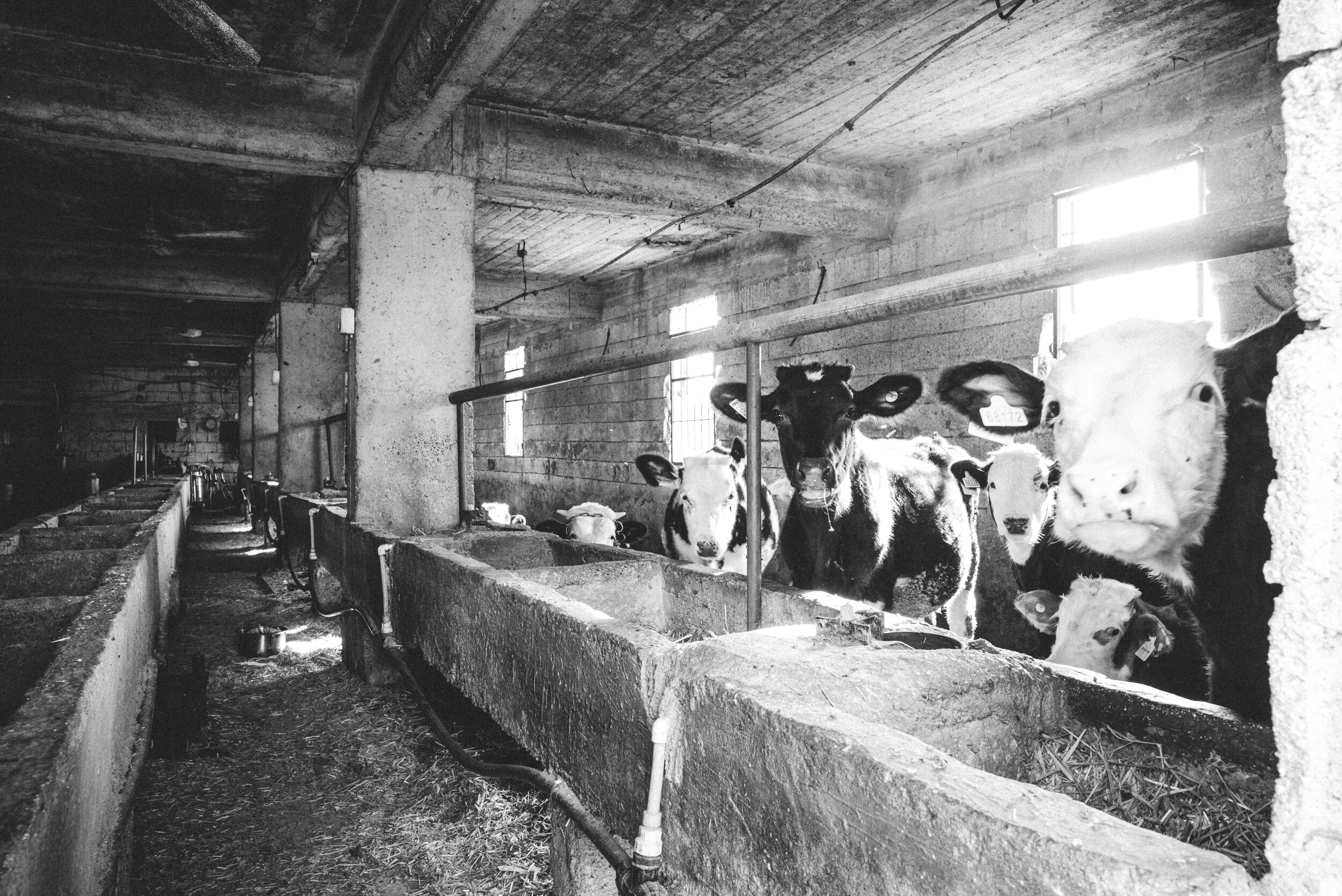

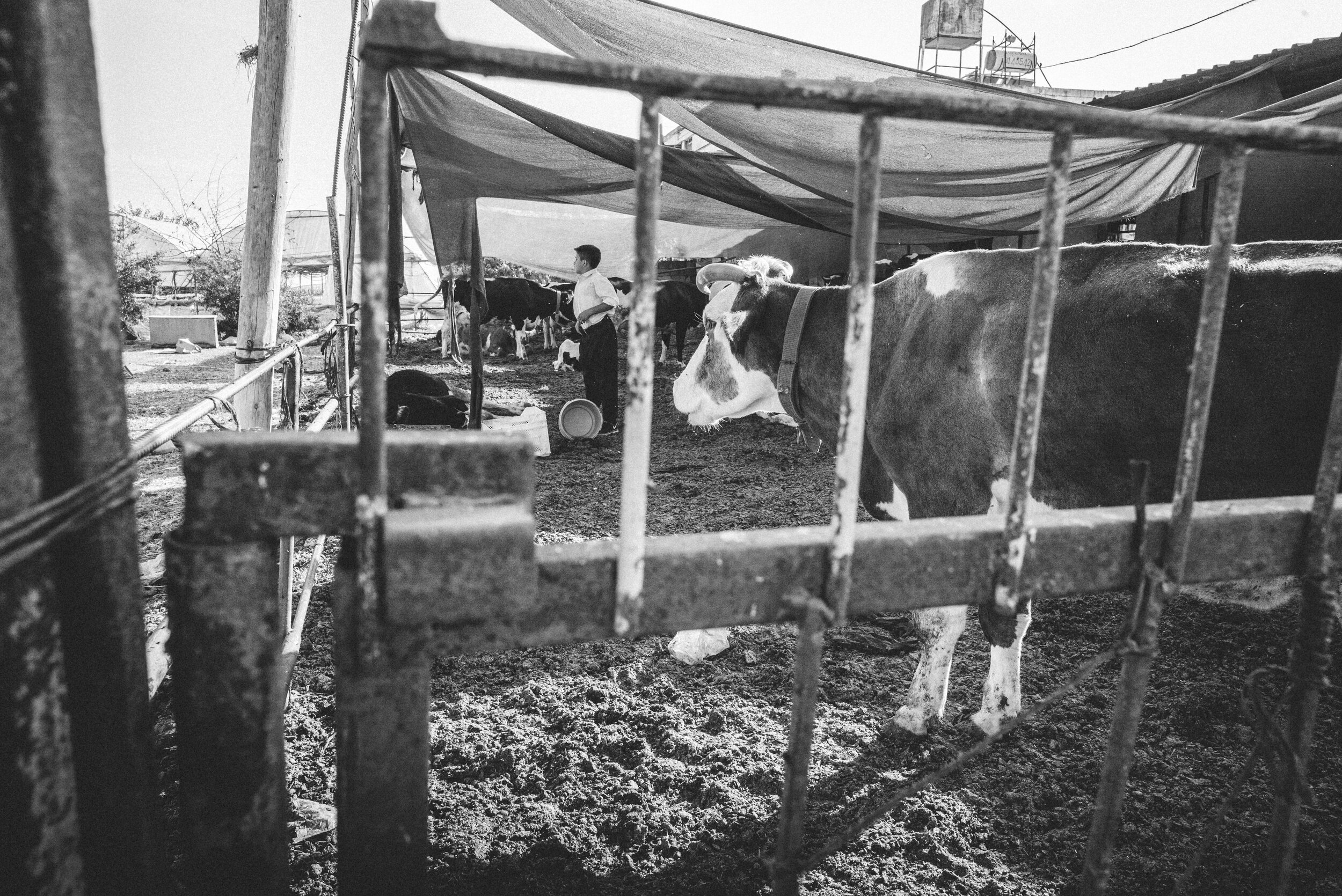

Hot and cold: Sure, if we are talking of actual temperatures and seasons, we come to the land. There is agricultural wealth here around Kilis, a long tradition of farming. Turkish farming families, the new generation of a workforce, have been moved out of the region, driven out of it by the way, by local and global economic pressures. Leek doesn’t sell at all, Ibrahim Yanaslan, a native to Kilis. The 50-year-old has been a farmer all his life, growing some other crops and keeping a few cows for milk. Seeing the war come from across the border and the money, life has gotten harder. But the land that he owns, 25 acres of it, cannot be let go to waste. It needs working. Lena and Hassan, both from Aleppo, are weeding one of Ibrahim’s fields.

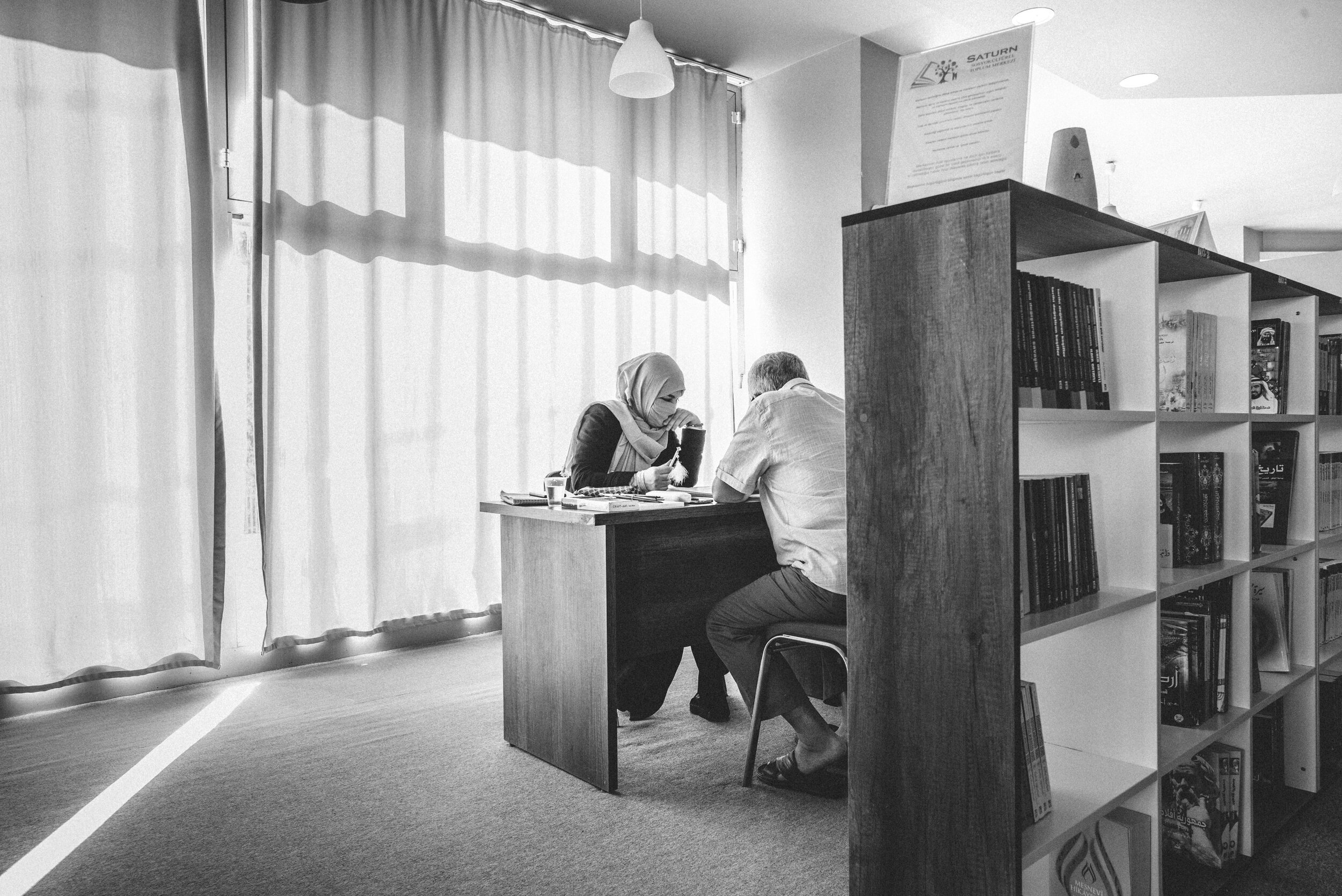

I think livelihood and family and (a personal sense of) peace are linked. This much has also became clear at Mehmet’s farm, in the rural outskirts of Kilis. Mehmet is a landowner, he inherited the estate from his father. Several years ago he set up a union with his neighbours to better manage market access and cooperation with local government and ngo's. His farm serves as a headquarter base for a skills training project for the Syrian refugees, who are taught to work the land. As skilled laborers they can contribute to the local economy. The new farming hands divide their time between theory classes in a (multicultural) classroom and work on the field. Lunch is distributed to the trainees each day; the participating farmers who supervise them come to the base to collect the packed lunches.

Hot and cold: As we have approached and then circled Kilis on this trip it is reported that Turkey-backed militia members have returned out of Syria, to be bussed to Nagorno-Karabach, with another conflict stirring.

Hot and cold: From places such as this - we have visited more of these limit-line towns - “you can feel Syria on the incoming wind”, as the saying goes that has been repeated to us by more than one conversational partner.

Hot and cold: The same categorization is used in the medical settings, as we have already learned in Reyhanli.

We visit another, more informal guest house for Syrian refugees medical patients, started by Adel Ado, a 40-year-old from Aleppo.His townvilla is located on the main, razor-straight road toward the border post. There are twenty beds here for fellow-countrymen who are in therapy, half of which are occupied. One of his in-house patients is actually beyond treatment, Ado confides to us. One of them is a double amputee, the man has not family or possessions left. Apart from the room in this scrappy care home, he has no place to go.

We sit outside on the concrete porch. One door, slightly ajar, leads from that into the house, where peeking in I see a working office, overflowing with dusty paperwork. We are early to visit the centre. Its residents are all still asleep.Ado will start to make his rounds after our chat. A pair of kittens stealthily play between the legs of the white plastic outdoor chair he has sat down in. The porch looks out over a plot of slightly sloping land - Ado’s passion project. He works its agricultural produce and sometimes, the patients lend a hand. It’s a heartwarming thing, working the hands, filling the land, emptying the head. Who knows what may grow back on it. Ado is currently trying to convince the Kilis municipality to allow him to continue cultivate an extra acre or so - or change, for them. He cannot hold back hot tears when he states, “The land is important. I lost my son in the war, and the home he lost it over will never be mine anymore.”

Hot and cold: It must be a disorienting experience, getting settled out of your own will, your own dictation lacking. Those who stay in Kilis - by the ten thousands - must feel ambivalent sometimes. In speaking to some of them, I get the sense of a community that exists in the city’s undergrowth, of a collective shadow of the city: with its own cultural centres, its own system of care its own economy. It’s like a coping mechanism for getting to know a new city and language, the very notion that possibilities might blossom again - if not for yourself, then at least for your next ones. It is a peculiar comfort in being instationary.

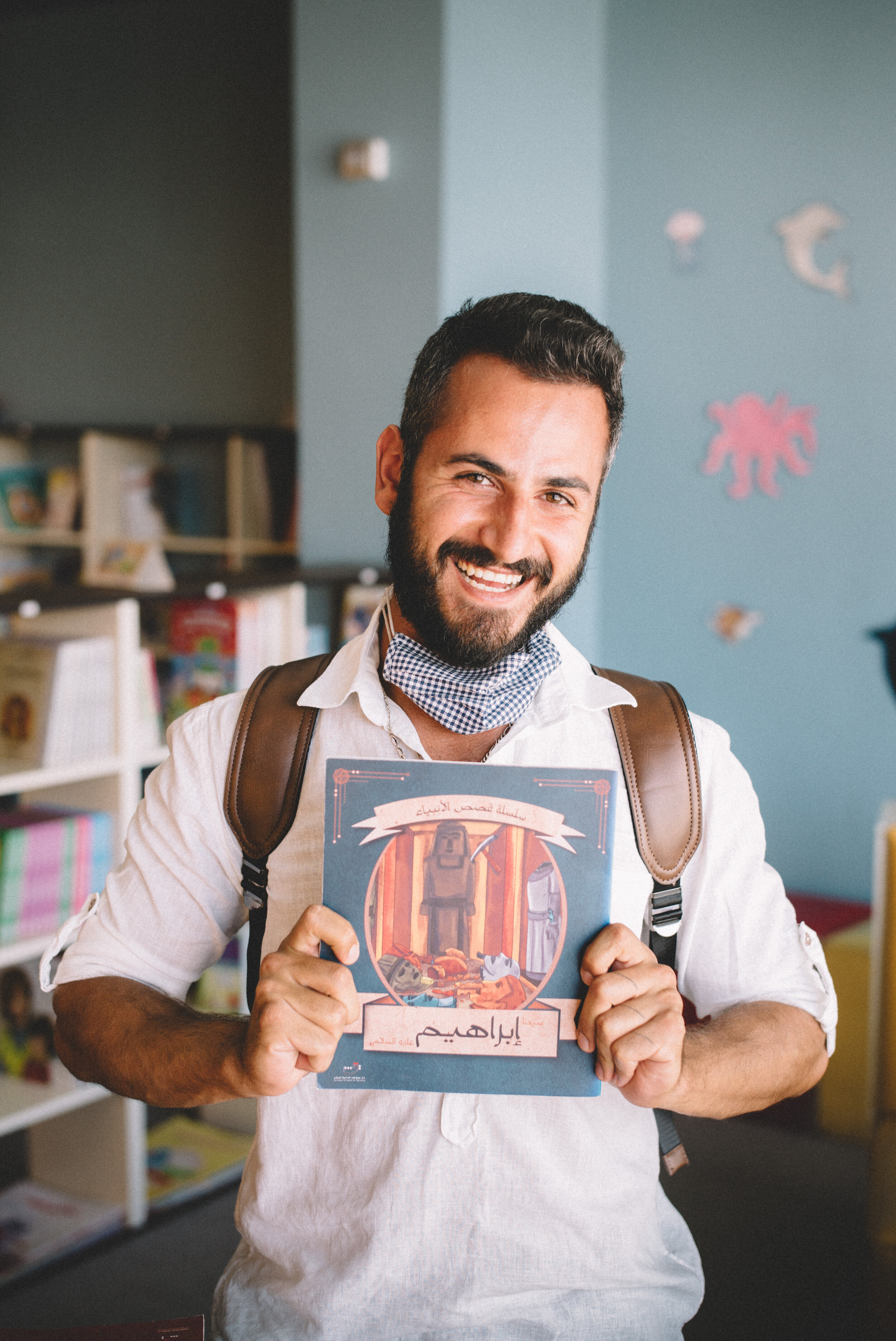

Those who are properly most capable of navigating both the shadow map and the possibilities-map of real-life in Turkey, are young Syrians. We visit a cultural centre for Syrian and Turkish youth that aims to give this population a sense of direction. We speak to Hammelde Abdoulghani, who runs a one-man book-lending, archiving and publishing operation out of a little cramped shop in a residential area.

We spend a delightful, special day with those from the Syrian diaspora who work on the importance of stories and the relief, or expression, of suffering that telling can bring.

Hot and cold: On our last day in Kilis, we visit with Moustafa, a gently protruding man, soft on the edges and with a smoldering sparkle in the eye. He tells us ‘no’ on the photos, so we sit still on our lush seats. His sons wait on us in the living room, when they are not looking onto their phones. Moustafa brought his whole family over. Continues to bring others over, and beyond, too. Forget Kilis’s temp point, the whole of Turkey is on the brink of collapse. Moustafa can feel it. Turmoil and insecurity are brewing, a pressure that is discernible for whoever he experienced enough problems of their own: like snakes coiling and curling on the bottom of a dried-up well. Difficult to say in that metaphor - I have projected it unto Moustafa’s short, intense answers and his facial expression - if Turkey is the well, or the slithering animals it contains, or the playing child that is playing nearby, in constant risk of falling in after a ball or some other plaything. This is how he explains: “Those who follow the news, know. You just watch the news, hear what is happening.”

What is happening is a geopolitical mess. (I feel like we’ve been riding of the back of it this whole month.) Turkey is barely holding on to the edges, a frayed but existing and functioning state, looking to tighten its grip. Outwardly it is asserting itself, it has to. “Even in this last year, one after the other, the other countries are coming for Turkey. It has to show itself to be strong, dangerous against them. Greece, France. The Russians have been pushing, pushing”, Moustafa knows.

Every morsel of the conflict in Syria finds its way into Turkey, in the form of soldiers, refugees, militias, wares. The remnants walk around here, Moustafa gestures vaguely to the living room window that offers a view of one of the city’s main streets. The people on there, do they understand that a real implosion could be forthcoming, the thing he warns of? He shrugs fleshy shoulders. “Of course a lot of people don’t pay attention. Or poor people, who might not follow the news, who have enough issues of their own.” If only they would have the luxury to pay a little more attention to the rest of the world, he thinks many of them would recognize the signs. After all, they have lived through such an event before. Internally, Moustafa thinks,Turkey cannot keep to hold on. “And if it does collapse, it will be worse than what happened in Syria. The reason for that is simple: everyone is already here. All the groups. Whatever is involved in Syria, here in Turkey they already have a foothold. It will be easy for them to fight each other here, openly.”

You’d think now is the time to get out then.

But the thing is, Moustafa is fine. He’s found his way. (And the way to profit from those remnants he sees floating around. That is how the world works - do we think of him as a bad guy now?) If anything, he will back to Syria if a new state comes tumbling down. He is good for now, and the goal is clear: to continue making money. Moustafa is working his way to a six-figure sum on his bank account. It will be enough to send his sons off - to school in Germany, a new life with an uncle in the UK, onwards from Turkey.